Helicobacter pylori bacteria infiltrate the stomach and the first part of the small intestine (duodenum), often leading to open sores known as peptic ulcers; many individuals living with this infection won’t show any symptoms at all.

Symptoms

Helicobacter pylori (aka “H. pylori “) is a spiral-shaped bacteria that lives on or in your stomach’s lining and causes most cases of peptic ulcers – sores in the lining of either your stomach or duodenum (first part of small intestine). It can also cause chronic inflammation and could increase your risk for certain forms of cancer.

This type of infection often goes undetected, so testing may be required in order to diagnose an infection. If symptoms do appear, however, they typically include stomach discomfort that feels like an ache or burning and usually manifests below your ribs in the center of the stomach; lasting several hours or days and worsening when you’re fasting until eating something can help relieve it.

The bacteria enter your body when you spit or have diarrhea and settle in your abdomen, where they alter how your stomach creates acid and weakening of stomach cells occurs. They release an enzyme known as urease (which you can learn about here) to lessen acidity of stomach acids while weakening cells further, increasing chances of injury from acid or digestive fluid such as pepsin; furthermore, their presence can result in sores or ulcers to form on the abdomen and duodenum linings.

Your doctor will likely conduct an endoscopy to confirm their diagnosis, which involves inserting a thin tube with a camera at its end down your throat and into your stomach and duodenum, sending images back up the tube onto a screen for viewing by your physician. They might also take a biopsy of your stomach lining to check for H. pylori or any other infections; in such a test you will be sedated prior to testing.

Diagnosis

H. pylori bacteria can be diagnosed by blood, breath, and stool tests; but your doctor may opt for an upper endoscopy instead, in which a flexible tube with a camera threaded down your throat into your esophagus, stomach and duodenum allows him to see what’s amiss with your tummy lining while collecting tissue samples to test for it as well as factors contributing to gastritis such as using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

The H. pylori bacteria produce an enzyme known as urease that alters acidity so they can survive, attaching themselves to the lining of your stomach and duodenum and causing inflammation resulting in sores (peptic ulcers) or inflammation of both (gastritis). While not everyone affected by H. pylori experiences symptoms, some may be genetically predisposed for this infection and show no symptoms at all.

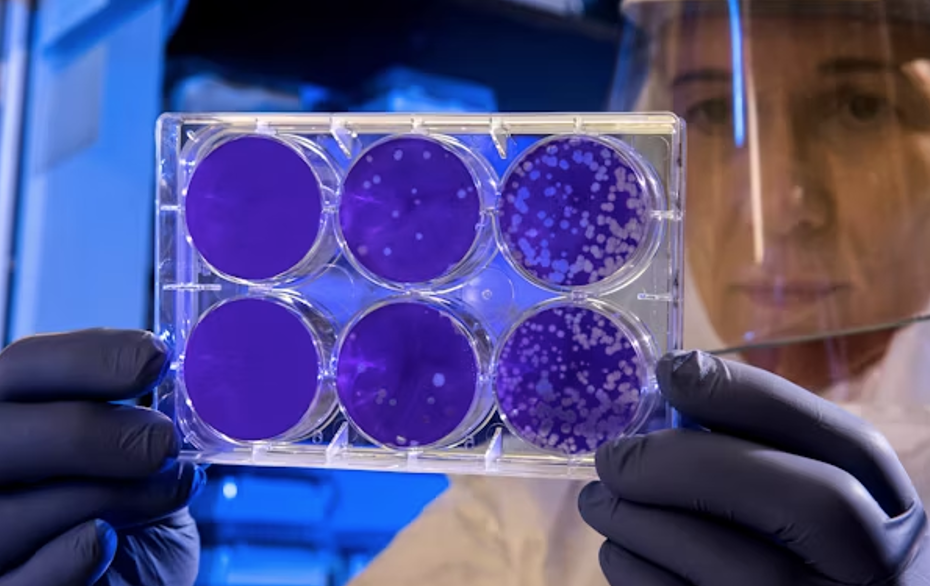

Histology and culture tests can also be used to confirm this type of infection in patients. Histology allows doctors to classify gastritis lesions and detect any associated malignant disease; while bacterial culture allows doctors to conduct susceptibility testing of potential antibiotic treatments against H. pylori.

Treatment

H. pylori infects many without symptoms yet can still damage the stomach’s protective lining and lead to complications like peptic ulcers. Medication can treat ulcers while also reducing inflammation and preventing new ones from forming; clearing away this bacterium reduces one’s risk for stomach cancer as well.

Blood, breath and stool tests can help diagnose an H. pylori infection. If symptoms exist, healthcare providers may arrange an endoscopy in order to view the inside of your body’s lining and small intestine, including any ulcers present.

Health care professionals may use various medications to eliminate bacteria. Most treatment for Helicobacter pylori regimens consists of antibiotics and acid-reducing drugs combined, with proton pump inhibitors, clarithromycin, amoxicillin or metronidazole being typical examples of triple therapy regimens that work effectively against bacteria. Acid-reducing drugs help keep the body’s acid at a minimum so the antibiotics can work more effectively against their targets.

Prevention

Antibiotics are typically prescribed to treat infections caused by H. pylori, but some strains have resistance. Many factors affect treatment success: regimen selection, patient adherence to multidrug therapies used, resistance of the H. pylori strain to those antibiotics prescribed and strain resistance itself.

H. pylori infects billions of people worldwide and is the primary cause of stomach ulcers and gastritis. But most individuals infected with H. pylori don’t develop symptoms, suggesting the bacteria are harmless; though how it got there remains unknown – researchers think the transmission occurs through drinking contaminated water, eating foods containing H. pylori or touching an infected finger to oneself.

Natural treatments have not been proven to eradicate bacteria, so they should only be utilized under medical supervision. According to studies, diet may help decrease your risk of reinfection; eating five to six smaller meals each day and avoiding foods which cause irritation can help – as can washing hands thoroughly after using the toilet and before preparing or eating food; it’s also vital that only safe water be consumed.